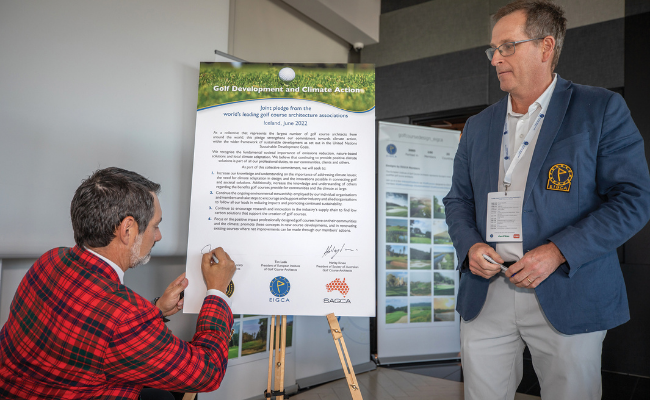

Golf made an eye-opening declaration to the world last year during a gathering of golf course architects in Iceland: “We recognize the fundamental societal importance of emissions reduction, nature-based solutions and local climate adaptation.” So stated a pledge signed by the world’s three largest associations of course designers. It went on to proclaim: “We believe that continuing to provide positive climate solutions is part of all our professional duties, to our communities, clients and others.”

The declaration might even seem radical, but that’s only if you haven’t been tracking how holistic modern golf course design has become. (Note the use of the word “continuing” in the declaration.)

“People think golf course architects are focused on the slopes of greens or where the bunkers go — and yes, those are all important,” says Jason Straka, who signed the climate pledge as then-president of the American Society of Golf Course Architects (ASGCA). “But our training crosses so many disciplines: agronomy, landscape architecture, flood control. And golf courses can be great sites for (biological) diversification. Most of us have training in the realm too.”

Given all that, the climate pledge may not be so surprising inside the golf industry, but it does send a broader message that the sport is aware of its responsibility to do its part to mitigate the effects of the climate crisis. Straka didn’t just sign the pledge as a matter of personal belief, although he has a long background in environmentally sensitive course design. He brought the issue to ASGCA leadership and received buy-in, and the pledge was signed by two other major associations: the European Institute of Golf Course Architects and the Society of Australian Golf Course Architects. In other words, the majority of golf course architects worldwide were represented by the three signatories that day in Iceland.

Does that mean that the entire golf industry is on board in accepting that climate change is largely the result of human action? Not necessarily. But Straka says that in a way it doesn’t matter. “There’s a myriad of sentiments about it,” he says. “Some are not convinced it’s manmade. But we as an industry have a customer base. Certainly my generation (Straka is 51) and younger are more aware, more environmentally active. The customer base cares. So, if you’re a smart businessperson, you’re going to do it whether you believe it or not. You’re selling, and people are buying.”

Forrest Richardson, the Phoenix-based architect known in SoCal for his work on such courses as Roosevelt in Griffith Park and Olivas Links in Ventura, echoes that: “It doesn’t matter where you stand on what we call climate change, because many of the same goals and outcomes of reducing inputs and resources in golf have terrific benefits to ROI and productivity. Being more efficient simply makes good sense.”

Richardson was present that day last summer in Iceland and supports the pledge. “Golf course architects have been very active over the past decade in helping clients reduce inputs, whether turf area, bunker area or by allowing the courses to take on a more natural, less-maintained theme. All this translates into less energy and, many times, less water use.”

BROWN IS THE NEW GREEN

Here in the Southwest, the need to conserve water in the face of climate change and prolonged drought is a given. That reality is catching on nationwide. Straka points to the decision by Golf Digest to add “firm and fast” to its criteria for ranking golf courses. “We’ve gotten away from the notion that everything has to look perfect. Brown is good,” says Straka. In fact, it’s difficult to find a golf course architect who doesn’t address the need to save water. San Diego–based Cary Bickler places “Environmentally sensitive new course designs” at the top of his list of services, followed closely by xeriscaping. “We’re being better stewards of water use now and addressing the need for faster play,” Bickler says.

Architects have a number of additional tools in their design quiver, says Straka. Turf reduction is one of them. Straka points to his renovation of Ambiente in Scottsdale as an example, taking the desert course from 210 acres of maintained turf down to just 90 acres. That saves water, of course, but the benefits go beyond that — depending on what replaces the irrigated grass. “We’re finding that one of the best carbon sinks is native grasses. Our native prairies were excellent at that. So we’re looking at how we can we naturalize areas with native plants and trees.”

Adds Straka: “We’re artists. We’re creating landscapes that are pretty to look at, and plants are part of that beauty. If you can use plants that are beneficial to the environment and also look pretty, why wouldn’t you?”

Then the effects multiply. Less fertilizer: Most fertilizers are petroleum-based. Less piping: Plastic irrigation lines are petroleum-based. More wildlife: Ambiente saw an increase in coyotes, bobcats and amphibians — which required some neighborhood buy-in. “But it proved that the work was effective,” says Straka.

In many ways, golf courses by their nature have a positive environmental impact, contends Forrest Richardson. “They benefit communities by filtering urban drainage, producing oxygen across their greenspace, and — perhaps most important — they break up the patchwork of concrete, asphalt and rooftops we are continually adding to the landscape.”

Then, harking back to the spirit of the climate pledge, Richardson adds: “If, through our work designing and redesigning, we can make a more positive footprint on society, I’m all for it.”