You get it a lot. You know — that squinty-eyed look from non-golfing friends when you wax poetic about your latest round, or about the beauty of a favorite course. “Golf?” the eyes are saying. “Seriously? Can we really be watering all that green in this day and age?”

Here’s what you can tell those scoffers. The USGA has announced an initiative that they’ve dubbed “15-30-45.” It’s a 15-year, $30 million commitment to provide ways for golf courses to reduce their use of water by as much as 45 percent. (Ask your skeptical friends if they have reduced their water consumption by 45 percent.)

As USGA CEO Mike Whan put it in his annual state-of-the-game address in February, “Let’s stop talking about sustainability and start putting our money and our effort where our mouth is.”

Acknowledging The Inevitable

Those $30 million dollars indicate that there is some merit to your friends’ point of view. There’s no doubt that golf courses have historically been water hogs. And despite our glut of rain and snow this year, we all know the big picture. Our underground aquifers have been severely depleted by years of drought — so much so that the ground itself in the Central Valley is sinking

The Colorado River remains in crisis, and the seven states of the Lower Colorado River Basin have been directed by the federal government to find ways to cut their use of the river’s water by as much as a third. Experts say it would take at least six straight years as wet as this one to replenish Lakes Mead and Powell. No one is betting on that possibility.

Golf courses will be a logical target of cutback mandates, which is why USGA consulting agronomist Brian Whitlark has been urging Western golf courses to get out ahead of the issue.

“Some golf courses operate under the idea that they will wait to cut back on water until regulators tell them to. That is a dangerous game to play,” says Whitlark. “When the time comes, regulators may not only tell them how much to cut but also how to do it. If leadership in the golf industry is not proactive… someone will dictate the rules for them, and golf courses will be in harm’s way.”

Phalanx Of Solutions

Proactivity is what the 15-30- 45 initiative is all about. It also signifies that the USGA believes that solutions are possible and, indeed, feasible. Many are already underway. Here are some of the key action areas that the USGA’s experts are addressing:

▪ Reducing irrigated acreage by removing turf in little-used areas and replacing it with low-water plants and hardscape.

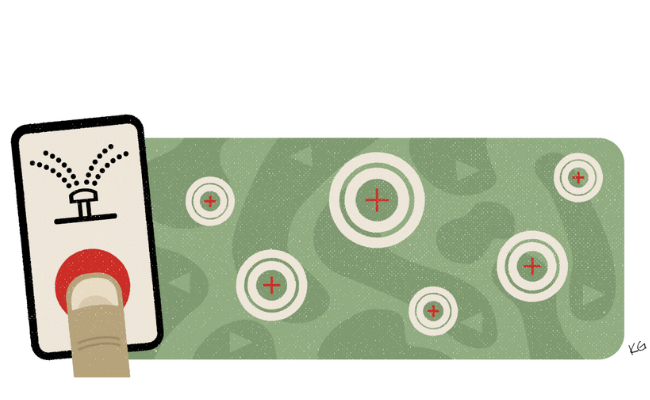

▪ Using sensors to determine when (and when not) to water, eliminating guesswork that wastefully drenches golf courses.

▪ Upgrading irrigation systems. “Golf courses can typically save six to eight percent just by raising and leveling sprinklers and replacing old nozzles,” says Whitlark.

▪ Using drip irrigation where possible, such as on teeing grounds. “There’s huge untapped potential in eliminating overspray,” says Whitlark. Subsurface drip irrigation can reduce water usage by 50 to 80 percent.

▪ Using recycled water. Irrigating with treated wastewater can reduce a course’s reliance on public drinking water supplies. Eight of the 11 LA City-owned courses already irrigate with recycled water.

▪ Turf conversions offer huge water-saving potential. The Valley Club of Montecito demonstrated that a decade ago by converting its cool-season turfgrass to a warm-season hybrid Bermuda that saves a huge amount of water. El Caballero CC in Tarzana underwent a conversion from ryegrass to hybrid Bermuda in 2021–22 that required a nine-month closure of the course, but resulted in a 25 percent water reduction. “It just wasn’t sustainable,” says El Cab General Manager and COO Phil Lopez. “Replacing the ryegrass was the biggest and best thing we could do as a club and as environmental stewards.” El Cab reduced its water consumption even more by ripping out acres of little-used turf and replacing it with decomposed granite, olive trees and native plants.

▪ New turf varieties on the horizon. As hybrid Bermuda grasses continue to prove their value, researchers continue to develop new warm-season turfgrasses. UC Riverside is leading the way in this research, focusing on Bermuda and Kikuyu grasses that are both drought-resistant and retain their color in winter. The USGA is among the supporting sponsors of that research, and the USGA’s Mike Whan envisions kicking that effort up a major notch or two: “We’re doing incredible research to figure out what we can do in a two-by-two-foot plot of land. Now it’s making sure we take that… and get it into the marketplace.”

▪ Eliminating overseeding. To keep courses looking emerald green in fall and winter, many golf courses, especially in the desert, spread ryegrass seeds over the existing bermudagrass turf that is going dormant. The problem is, the ryegrass needs heavy watering to germinate. Eliminating overseeding can save 1.5 to 2 acre-feet of water per acre of grass.

Managing Expectations

This may be the biggest challenge of all. Does every course in the West need to resemble Augusta National in April? Does green turf always present a superior playing surface? Many of golf’s more wasteful practices are in response to member pressure to keep their courses green.

“We need to change the narrative around what is considered a high-quality playing experience,” says Whitlark. “In America, the bar is set around lush, green conditions. We need to change that. The new bar should be set around full turf cover and firm playing conditions. If we move away from lush and green to a playing experience where we’ve got grass to play on, the grass is firm and we get good ball roll — man, let’s play golf!”

If the USGA can help encourage golfers to not only tolerate but prefer that kind of experience, and at the same time teach course managers to better manage their dwindling water allotments, that will be $30 million well spent — and it will bode well for the future of the game.