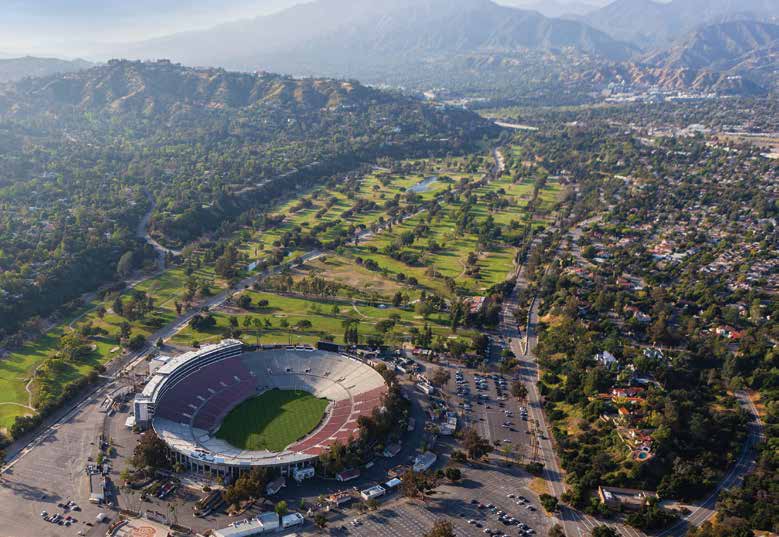

Millions around the world recognize it as the place where thousands of cars are parked for the Rose Bowl game every New Year’s Day. Golfers recognize it as one of the oldest and best municipal golf courses in California — two courses in fact; one a 7,104-yard championship layout (Koiner or No. 1) that hosted the 1974 USGA Amateur Public Links Championship; and the other a 6,022-yard layout (E.O. Nay or No. 2) that is as popular if not more so with the mid- and high-handicappers that dominate golf’s ranks. Together they make up the Brookside Golf Complex.

Those in the golf business recognize Brookside as a 36-hole golf complex on the cutting edge of meeting the municipal game’s challenges attached to an iconic football stadium bent on ensuring that it doesn’t go the way of the Orange or Cotton Bowls, relics consigned to the junk heap of history.

And the two are literally attached, not just contiguous. They are parts of a Pasadena Arroyo Parks and Recreation District managed on behalf of the City of Pasadena by a Rose Bowl Operating Company (RBOC) composed of City Council and designated stakeholder appointees. The RBOC hires staff to manage the affairs of the stadium and the golf courses; some of the functions are sublet to the private sector per specific contract terms.

Koiner opened for business in 1928. E.O. Nay opened nine holes in 1932 and added nine more in 1938. Both were designed by storied golf course architect William P. Bell. They were funded by multiple public and quasi-public sources, among them the Pasadena Chamber of Commerce, Pasadena Municipal Light and Power and the Pasadena Public Employees Union — a testament to the value local governments, businesses and recreational communities placed on publicly accessible golf in those days.

Enterprises that get their start at the dawn of a Great Depression immediately followed by a World War know something about how to cope with difficult circumstances. They aren’t flummoxed by business cycles, epochal changes, societal shifts and the like. And Brookside has endured many of them, the last one in the mid-1980s when Pasadena realized that its model of municipal golf management had fallen behind those taking advantage of the revenue generation and capital improvement benefits of contracting out their courses to private companies in exchange for control.

“WE ARE LITERALLY AT A CROSSROADS MOMENT, WHERE WE SIMPLY HAVE TO FIND CREATIVE WAYS TO GENERATE THE REVENUE NEEDED TO OPERATE FIRST-RATE GOLF COURSES.”

— RBOC Director Darryl Dunn

It wasn’t smooth or easy; change never is. But after the dust settled and the political embers died down, the city entered a 30-year era in which the American Golf Corporation leased the complex and assumed all risk and expense of operation, performed capital improvements as a function of its fee-collecting responsibilities and remitted nearly $70 million to the RBOC in rental payments, roughly $30 million of which represented net proceeds to the city.

REVENUE SQUEEZE

As has been chronicled many times over, that era has ended, replaced by an era in which water, energy, compliance and labor costs have surged multiples of the Consumer Price Index and beyond the capacity of the golf market to absorb.

“We’re in a revenue squeeze created by spiraling expenses and a rounds squeeze aggravated by economic changes,” says RBOC Executive Director Darryl Dunn. “We are literally at a crossroads moment, where we simply have to find creative ways to generate the revenue needed to operate first-rate golf courses.”

Forty-year city/RBOC and Brookside Golf Course veteran Dave Sams, who last year retired as director of golf operations, agrees with Dunn, but points out that Brookside has been the recipient of roughly $6 million in golf course improvements since 2003, some of it going toward the enormous water feature on Koiner’s sixth fairway that was built in anticipation of receiving recycled water from the nearby Glendale/Los Angeles Plant, a project that is now in jeopardy of collapsing for reasons beyond the capacity of the City of Pasadena to control.

“It’s hard to run a first-rate golf course when your water allotment is cut back 28 percent,” says Sams.

And there’s the rub: how to run first-rate golf courses in an era no longer characterized by a public sector willing to expend public monies in the way that Pasadena so routinely did to build the Rose Bowl and Brookside Golf Courses in the first decades of the 20th century and a market no longer capable of enticing the private sector to make the kinds of investments and assume the level of risk so routine in the 1980s and ’90s.

If you’re the RBOC, you take advantage of the situation posterity has bequeathed you — an iconic football stadium, a 36-hole golf complex, the Arroyo setting, and an eclectic mix of open space recreational activities — and conduct as many revenue-generating events as the surrounding affluent neighborhood will permit and the golf courses can handle, while still delivering a quality golf experience. In short, a balancing act easier to describe than execute. And to effectively execute it, you renegotiate your risk-transferring lease agreement with the American Golf Corporation into a management agreement in which the city gains complete control by assuming all business risk and responsibility for capital improvements.

GETTING IT RIGHT

The Arroyo is a neighborhood that overwhelmingly rejected NFL entreaties that would have delivered millions of dollars in ancillary revenue. It’s also a neighborhood that has kept a tight lid on the number of outside events that now routinely take place — e.g., annual arts festival, vegan festival, next May’s Rolling Stones concert.

More events would equal more revenue, but revenue is the means to the end in the Arroyo, not the end itself. And part of that “end” is a quality golf experience — “a balancing act between the integrity of the golf courses and the conduct of outside revenue-generating events,” as RBOC’s Dunn puts it. “We don’t want to lose the confidence of the golf community.”

“EXCELLENT CONDITIONS, A GREAT LAYOUT — THAT’S THE BROOKSIDE BRAND. LOSE THAT AND YOU LOSE WHAT MAKES BROOKSIDE SPECIAL.”

— Two-time Pasadena Champion Dan Sullivan

The Arroyo neighbors have never been shy about expressing their views. Their stake in the “balancing act” is visceral. With less at stake, Brookside’s golfers have been less vociferous, but in terms of how golfers usually express their views — frequency of play — it isn’t a stretch to attribute at least some of Brookside’s recent rounds erosion to the challenges posed by water restrictions and outside events.

A twenty-year Pasadena resident, two-time Pasadena City Champion, and three–time SCGA Player of the Year (2013, 2016 and 2017), Dan Sullivan says that he joined the Brookside GC and played every weekend there for years, because the facility was simply the best conditioned and maintained public golf course in the region, not to mention a worthy test for a player of his caliber.

However, Sullivan says, he and many of his championship caliber cohorts have drifted away from Brookside as conditions have ebbed.

“Excellent conditions, a great layout — that’s the Brookside brand. Lose that and you lose what makes Brookside special,” he says. And Sullivan would hate to lose that, because he is convinced that playing in a club with so many champion-ship-caliber players on a course of such quality made him the player he is.

Sullivan predicts that the RBOC will be hearing more and more from area golf-ers as this “crossroads” moment plays out. “There is just too much history and emo-tional attachment to walk away,” he says.

If Sullivan is right, matching that “attachment” with Dunn’s commitment to maintaining the “confidence of the golf community” could be just the mix that preserves the “Brookside brand” he describes.

Sams is right. It’s hard to manage first-rate golf courses on water restrictions. It’s even harder to manage them while using their fairways for festivals and parking lots. But it’s impossible to manage them without adequate resources.

Generating those resources while maintaining the integrity of the product … that’s the challenge. The Rose Bowl and Brookside have conquered much bigger challenges in their century-long partnership. Smart money is on them getting this one right too. ▪